I thought it might be interesting (and helpful to many) if I posted in-depth information about some of the main characters in “Fate.” These characters are based actual living, breathing people in the 19th-century, scholars do know something about their points of view, attitudes, and general personalities. I had the honor of tweaking these attributes further in my novel of course, and so it will be my take on them that I write about here. I will write about many over the coming weeks, starting today with Tchaikovsky’s loyal servant, Aleksei Sofronov. (Note: Since Russian language translations are merely English written phonetically by the way a word sounds, Aleksei is sometimes written Aleksey.) For those readers who flinch every time they come across Russian names, these short characterizations should help introduce them to my characters in a simpler way.

Aleksei Ivanovich Sofronov

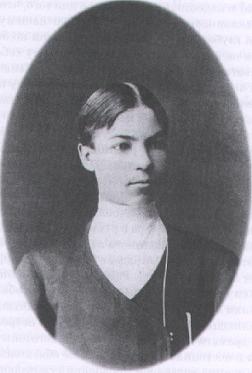

Aleksei Sofronov (young)

Aleksei’s middle name of Ivanovich is typical of the way the Russian culture automatically assigns them. It simply means that this particular Aleksei was the son of “Ivan.” Now that we have that out of they way, let me add that Russians adore nicknames and refer to people by them as soon as a certain level of familiarity has been achieved. The usual nickname for the proper name of Aleksei is Alyosha, and that is precisely what Tchaikovsky called him whenever saying his name out loud, or writing it in an affectionate way.

Aleksei was one of my favorite characters from the very start of my “Fate” book project and so I was very careful in my writing of him. Fortunately, he turned out even better than I had hoped. I simply adore him now and guess that most readers will feel that same. I knew he would be an important character but when I started the novel I had no idea just how important. He is integral to my story, as he was to the great composer’s life.

He is only “mentioned” in the first section of my novel, and does not appear as a character until well into the story. This is because he is still a young boy at the beginning, and new to Tchaikovsky’s service. These facts made him unnecessary to the story at hand. A bit later when he does appear, he is almost immediately thrust into the middle of things. He helps Tchaikovsky dress “plainly” so that the composer can go to the premiere of his ballet Swan Lake without being recognized. Aleksei’s immaturity is evident during this time and continues well into the scenes where the composer seeks to marry Antonina. He is often frustrated with the composer’s demands, which sometimes confound him, but clearly has a strong loyalty to him. He is not meek with Tchaikovsky, and speaks out when necessary. Still, there is an innate kindness about him, one that seeks to please his master.

By the time he and Tchaikovsky are in Switzerland and later Florence, Italy, I depicted him as the teenager he was and the man he was becoming. Aleksei now understands that the composer depends on him greatly, more than anyone else in his life, and not just for everyday errands. He has learned that Tchaikovsky’s health, melancholy, and mental well-being depends on his gentle service. I did not mention any past [possible] sexual contact between them because it was not important to my story and also because it would certainly not have been a love affair. If sexual contact had occurred between them it undoubtedly would have been the typical servant-type of gratification commonly practiced at the time, even by heterosexual men with their underage male servants. This is because the culture of the time accepted pre-pubescent males as something closer to female. This is obviously something today’s culture no longer accepts.

Once Aleksei is grown to manhood and sexually active [with females] himself, I devised a conversation between him and Tchaikovsky so that both characters could start on a new footing that would definitely no longer include the duties of sexual gratification and that would also show a change in their common relationship – one that was respectful and affectionate as two males regardless of their sexual persuasions. Much of the internet incorrectly defines Tchaikovsky’s complimentary closings in his correspondences as sexual seemingly to make him seem extra gay and having homosexual relationships with apparently everyone. The truth is that it was common for the composer [and others] to write a send off like, “I kiss your hands,” or “I kiss your face,” before signing his name. This was poetic only, and was meant to show affection to the recipient, nothing more.

As for Aleksei’s knowledge of the musical works being composed at this time, I sought to show some level of awareness on his part. After all, he and Tchaikovsky were together day and night, living together for years, and Aleksei would have been in an important supportive role of the works the maestro was creating.

By the time Aleksei is faced with being drafted into the Russian army, the close relationship between master and servant should be more than evident in my novel. I feel that my writing of these events is true to the feelings of both parties and not overstated. Tchaikovsky was devastated at the idea of Aleksei being sent away from him, especially after so many years of familiarity, something not easy for the shy composer. He must have wondered if he would ever be that close to anyone ever again.

I will stop my analysis here so as not to cause any spoilers but please feel free to contact me if you have unanswered questions or if you desire my opinion of their relationship after this mid-point in the novel.

Best regards, Adin Dalton

Discover more from Fate - The Tchaikovsky Novel

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.