‘Fate – The Tchaikovsky Novel’ has more than a few memorable characters, almost all of whom were living, breathing people in the late 1800’s.

If you’re curious about them or just want to know more after reading the book, you’ve landed on the right page. The following are all written by me. More of these articles will posted in the future as well.

I thought these might be helpful to many readers who just want to know more. While Tchaikovsky scholars do know something about these folks’ points of view, attitudes, and general personalities, I of course had the honor of tweaking their attributes further in my novel. It will obviously be my take on them again here.

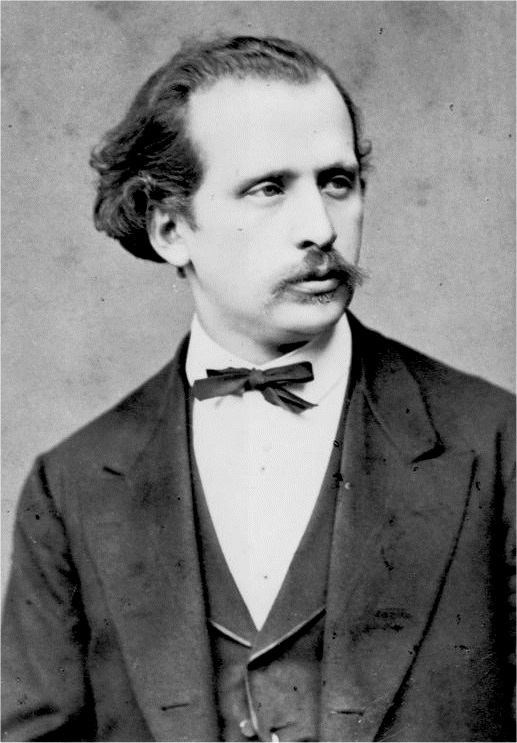

Nikolai Rubinstein

In “Fate,” one of the very first characters introduced is Nikolai Rubinstein. As a composer and talented musician, Rubinstein was quite well known in his day and through his work was granted the directorship of the Moscow Music Conservatory where the young Tchaikovsky was hired to teach. (Tchaikovsky’s fame undoubtedly played a part in how history has treated Rubinstein, completely overwhelming the memories and mentions that may have come to him had circumstances been different.) Nevertheless, Rubinstein was important in the musical circles of his time and held great power over all concert performances in Moscow, inside and outside the conservatory. His opinion of a certain musician could make or break their career. One sees this very thing at the beginning of the novel, with Rubinstein granting Pyotr ‘s request of having young Sergei Taneyev play the Piano Concerto in concert before the public.

While Nikolai was clearly one of Pyotr’s harshest critics, it’s obvious that this was merely to challenge the composer’s talents. In reality and in the novel, there’s a mutual respect between these two men; they worked together on operas and orchestral pieces in a partnership that, in hindsight, was very important to Pyotr’s development. And though the shy composer was greatly intimidated by Nikolai, he later discovers him to be one of the most loyal allies he could have.

One last thing before I give away too much… let me remind readers that it was Nikolai who had a close acquaintance with the wealthy Nadezhda von Meck for years. He must get credit for her discovery of Pyotr. It was also Nikolai who recommended then-student Yoself Kotek to von Meck to fill an empty spot in her musical ensemble. Many events that come together later were directly due to Nikolai Rubinstein.

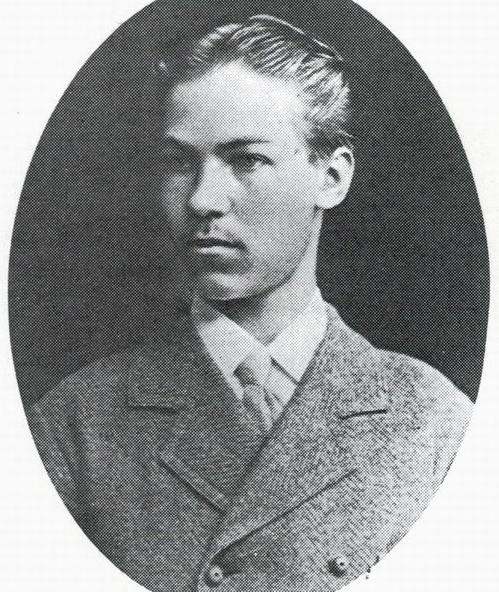

Anatoly Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Anatoly (and Modeste) Tchaikovsky were Pyotr’s younger [twin] brothers. It is clear that the composer adored them both, seeing them raised from infancy as he did. He visited them frequently when they were enrolled and living at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence in Saint Petersburg and could not have missed the obvious fact that while Modeste was showing strong homosexual tendencies (of which they discussed on more than one occasion) Anatoly was decidedly not. His penchant for the female sex was clear, and in many ways must have provided some comfort to Pyotr. During their teenage years Pyotr was in his mid to late twenties and trying to balance the needs and desires of his own sexuality with a simultaneous shame and disgust of it.

Of these three brothers, only Anatoly ended up embracing a career in legal theories for which the school had prepared them. He went on to become a competent attorney is Saint Petersburg and later rose to a moderately powerful position in politics as the Governor of Tiflis. By the time of his governorship, Pyotr was one of the most celebrated composers in Europe (think near rock-star status) and definitely helped the governorship come about.

While usually busy with his career, Anatoly found time for his family, attending gatherings at his sister’s estate at Kamenka where various family members would come for days or weeks at a time. The Tchaikovsky siblings maintained love for one another throughout their lives, undoubtedly influenced by their highly emotional and exceedingly loving father, Ilya.

Readers of my novel will already know that Anatoly eventually took a wife… an event that must have pleased Pyotr very much (that is, until he got to know her.) Praskovya, was from a well-to-do family and had a pushiness to her personality that had to have been exceedingly off-putting to Pyotr. Even so, Pyotr would have done all he could to get along with her in order to please his younger brother.

Readers of my novel will already know that Anatoly eventually took a wife… an event that must have pleased Pyotr very much (that is, until he got to know her.) Praskovya, was from a well-to-do family and had a pushiness to her personality that had to have been exceedingly off-putting to Pyotr. Even so, Pyotr would have done all he could to get along with her in order to please his younger brother.

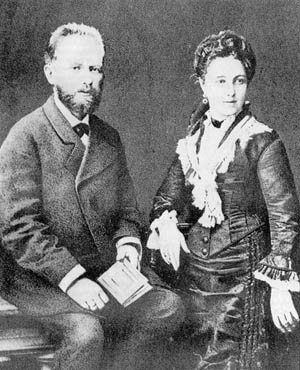

Yosef Kotek (with Pyotr)

Yosef is one of my favorite characters, especially of the ones romantically involved with Tchaikovsky. Also spelled Iosef or Josef in phonetically-translated Russian, this young man was known to be a former student from the Moscow Conservatory where the composer taught music during his late twenties to early thirties. Yosef was fifteen years his junior but clearly had a romantic connection to his professor. In my novel Pyotr Ilyich, we visit a period where Yosef has returned to the conservatory for the express purpose of visiting his former professor. He had recently been employed by the wealthy Nadezhda von Meck as a violinist in her private music ensemble and was anxious to catch up with Tchaikovsky. (As my readers know, Nadezhda eventually becomes the composer’s benefactor so one might wonder if her connection to Yosef is just a strange coincidence… It seems less so when one realizes that Nadezhda was well acquainted with Nikolai Rubinstein, the Conservatory Director, who obviously recommended Yosef to her when she inquired about employable musicians.)

Since Yosef is one of the few people who attended the infamous wedding, it became clear to me that his involvement with Tchaikovsky had become much more than just sexual. Yosef had stood by him through his entire courtship of Antonina, which I admired him for greatly, and thus decided to write him as an especially caring soul. This was love, not sex.

Later in my story, when the two are no longer involved but are working together on the Violin Concerto, I needed to show a definite maturing on the part of Yosef. I accomplished this by having him confide in Tchaikovsky in regard to his bout with syphilis, and his questioning of the composer’s judgment in regard his wanting to dedicate the concerto to him. As these were all true facts, they felt right being included in my story. –I will stop my character analysis here to avoid any spoilers which may come up!

space

The young lady who quite literally set out to ensnare Pyotr Ilyich is someone whom I love to hate. She was thrilling to write, constantly balancing on that tenuous line between sanity and insanity. I do believe that’s how it must have been for her most of the time. She was seemingly a very weak person, trying to make her idealized dreams come true by manipulation. Even if successful that can never be an actual dream come true. She was grasping for something she could never possess and yet was intent upon doing it.

Her threat of suicide if Pyotr did not agree to marry seems to have actually happened. This of course made him feel trapped, nevermind that he was clearly a homosexual. The events on their honeymoon which I portray in Fate also really happened, save for those moments when they are alone together. Those obviously had to be imagined. Their honeymoon was one of the most emotionally difficult chapters to write and filled me with great sadness and nervousness. I’m not sure why, but it is interesting for me to reflect on now. Perhaps I simply felt bad for both of them knowing the grave mistake that they had made.

My favorite scene to write regarding Antonina is when she suddenly reappears in the story, peeking through the draperies of a lonely flat as she works to spy on Pyotr’s brother in St. Petersburg. This too really happened.

I just wanted to touch on her a bit here so as not to give too much away for those who have not read the entire book yet. Those who have finished it know only too well that Pyotr was never really rid of her. He called the marriage ‘the biggest mistake of his life’ and referred to her in his letters as ‘the reptile.’

space

Aleksei Sofronov

Aleksei’s middle name of Ivanovich is typical of the way the Russian culture automatically assigns them. It simply means that this particular Aleksei was the son of “Ivan.” Now that we have that out of they way, let me add that Russians adore nicknames and refer to people by them as soon as a certain level of familiarity has been achieved. The usual nickname for the proper name of Aleksei is Alyosha, and that is precisely what Tchaikovsky called him whenever saying his name out loud, or writing it in an affectionate way.

Aleksei was one of my favorite characters from the very start of my “Fate” book project and so I was very careful in my writing of him. Fortunately, he turned out even better than I had hoped. I simply adore him now and guess that most readers will feel that same. I knew he would be an important character but when I started the novel I had no idea just how important. He is integral to my story, as he was to the great composer’s life.

He is only “mentioned” in the first section of my novel, and does not appear as a character until well into the story. This is because he is still a young boy at the beginning, and new to Tchaikovsky’s service. These facts made him unnecessary to the story at hand. A bit later when he does appear, he is almost immediately thrust into the middle of things. He helps Tchaikovsky dress “plainly” so that the composer can go to the premiere of his ballet Swan Lake without being recognized. Aleksei’s immaturity is evident during this time and continues well into the scenes where the composer seeks to marry Antonina. He is often frustrated with the composer’s demands, which sometimes confound him, but clearly has a strong loyalty to him. He is not meek with Tchaikovsky, and speaks out when necessary. Still, there is an innate kindness about him, one that seeks to please his master.

By the time he and Tchaikovsky are in Switzerland and later Florence, Italy, I depicted him as the teenager he was and the man he was becoming. Aleksei now understands that the composer depends on him greatly, more than anyone else in his life, and not just for everyday errands. He has learned that Tchaikovsky’s health, melancholy, and mental well-being depends on his gentle service. I did not mention any past [possible] sexual contact between them because it was not important to my story and also because it would certainly not have been a love affair. If sexual contact had occurred between them it undoubtedly would have been the typical servant-type of gratification commonly practiced at the time, even by heterosexual men with their underage male servants. This is because the culture of the time accepted pre-pubescent males as something closer to female. This is obviously something today’s culture no longer accepts.

Once Aleksei is grown to manhood and sexually active [with females] himself, I devised a conversation between him and Tchaikovsky so that both characters could start on a new footing that would definitely no longer include the duties of sexual gratification and that would also show a change in their common relationship – one that was respectful and affectionate as two males regardless of their sexual persuasions. Much of the internet incorrectly defines Tchaikovsky’s complimentary closings in his correspondences as sexual seemingly to make him seem extra gay and having homosexual relationships with apparently everyone. The truth is that it was common for the composer [and others] to write a send off like, “I kiss your hands,” or “I kiss your face,” before signing his name. This was poetic only, and was meant to show affection to the recipient, nothing more.

As for Aleksei’s knowledge of the musical works being composed at this time, I sought to show some level of awareness on his part. After all, he and Tchaikovsky were together day and night, living together for years, and Aleksei would have been in an important supportive role of the works the maestro was creating.

By the time Aleksei is faced with being drafted into the Russian army, the close relationship between master and servant should be more than evident in my novel. I feel that my writing of these events is true to the feelings of both parties and not overstated. Tchaikovsky was devastated at the idea of Aleksei being sent away from him, especially after so many years of familiarity, something not easy for the shy composer. He must have wondered if he would ever be that close to anyone ever again.

I will stop my analysis here so as not to cause any spoilers but please feel free to contact me if you have unanswered questions or if you desire my opinion of their relationship after this mid-point in the novel.

Marie (Laundress at the boarding house in Clarens, Switzerland)

Of all the characters in “Fate,” Marie might be thought of as one of the last ones to ever be chosen for a character analysis. Her somewhat brief (but important) appearance in the story might even convince readers that she is a fictionalized character inserted for the sole purpose of showing Tchaikovsky’s valet, Aleksei as having firm heterosexual tendencies. The fact is that Marie, the shy laundress in Clarens to whom Aleksei is passionately attracted, was very real indeed.

It was necessary for me to write her as realistic as possible, especially since she was a living breathing person whose path crossed so significantly with Tchaikovsky’s. I merged the daily flirtations of Marie and Aleksei with the composer’s rehearsals (with musician Yosef Kotek) of the famous Violin Concerto. After all, there was more than just music practice going on that spring. How do we know this? I will explain.

Found in some of Pyotr’s diaries is the evidence that Aleksei was responsible for the pregnancy of the young girl. The two men got news of it after they returned to Russia and while Aleksei never saw Marie again, a monetary connection was established. Pyotr felt somehow responsible for the girl’s plight and supported her financially for many years.

I was tempted to include this information in my novel but finally decided that it wasn’t necessary. I felt I had painted Tchaikovsky’s “good character” and “self respect” sufficiently enough to where this particular generosity would have simply been redundant. I hope readers enjoyed learning about it here.

It is clear from photographs that Aleksandra, Tchaikovsky’s only sister, was a truly beautiful woman. With five brothers (both older and younger) she was doted upon and adored by their father Ilya. Their mother (also Aleksandra) died when she was twelve, leaving the father to take care of his many children alone. Nanny’s were employed of course…while not wealthy, the Tchaikovsky family had means enough to afford such a luxury.

The common Russian nickname for Aleksandra is Sasha, and that is exactly what her family called her. (As for her last name of Tchaikovskaya, it gets the necessary “aya” on the end to denote a female or feminine version of the name. This becomes a “middle name” when one marries.) Aleksandra married a gentleman named Lev Davydov who was five years her elder and from a good family. Of course, when Aleksandra took the Davydov name it became Davydova to denote the feminine version. Hence her name: Aleksandra (Sasha) Tchaikovskaya Davydova.

Sasha, as I will call her here, is one of my kinder, gentler characters in “Fate.” She is sensitive, caring, and highly intelligent, and devoted to her husband Lev and their seven children. Their working estate was in an area called Kamenka and was some distance from the main cities of Moscow and Saint Petersburg. This is why it is always quite a journey (by train and then carriage) for Pyotr to come and visit his nieces and nephews. I will not go into Sasha’s life too deeply here so that I do not cause any spoilers for the book but trust me when I say that it was extremely eventful and worth reading about in my novel.

Almost all of Sasha’s scenes in “Fate” were based on actual moments in her life, including the remarkable scene where the notorious Antonina comes to stay with the Davydov’s at Kamenka. This was accurately portrayed, right down to Antonina dripping blood on Sasha’s sofa because she had nervously bitten her fingernails so short.

It is also true that Sasha was much more tolerant and understanding than her husband Lev when it came to Aleksei staying in Pyotr’s own room whenever the two visited Kamenka. It’s clear that Lev either suspected or was convinced of the composer’s homosexuality and wanted all appearances regarding their visit to be proper. He undoubtedly also harbored some God-fearing traits that would have made his opinions on this matter even stronger. This is what I strove to portray in the book. [Read my Character Analysis part 1 for more on the Aleksei-Pyotr sexual relationship.

It is evident from the actual correspondences between them that Pyotr loved Sasha deeply. Their close, affectionate relationship shows that the composer was not a woman-hater by any means, even though one might get that impression from his spiteful relationship with his wife, Antonina.

Who could look at a photo of Eduard (pronounced Edward) and not immediately assess that he was definitely some kind of troublemaker? That was my first impression. (The photo here shows the famed conductor in one of his friendlier moments.) His pointed features and intense, beady eyes lent a sinister aura about him in every photo I looked at. When I learned more about the man behind the face, I found my impression to be correct. He was ambitious to a fault, pedantic by nature, and certainly not a man to be trifled with. With these things in mind, I portrayed him (correctly) as one of Tchaikovsky’s talented musician friends but added a certain intimidation factor between them. The shy composer must have been somewhat wary of Eduard, especially in their later years when Napravník had much power as the principal conductor of the Imperial Theatres.

Napravník was a Czech musician from a poor family who was fortunate to attend the Saint Petersburg Musical Conservatory (where he met fellow student Tchaikovsky) and who settled in Russia to continue his career. He rose quickly through the ranks, undoubtedly elevated from his successful performances conducting the young composer’s first operas.

When my readers first encounter Eduard Napravník, he is already at the height of his powers. Tchaikovsky is clearly nervous to be in his presence, and the sinister conductor’s huge ego is laid bare on the page. This was by design of course; I wanted to show him as a nemesis to Tchaikovsky. One may even get the idea that he will play an important role in the illegal trial to come. That could be… but I dare not give anymore away. Suffice it to say that Napravník comes and goes throughout the book and always leaves the reader wanting more.